I’ve started a newsletter and I’d love you to read it. Sign up here:

I struggle with my limitations. I’m not sick like I was in 2019. I haven’t had trouble with the mechanics of walking since I last flew up to Auckland in February. I don’t have days and weeks of migraines every month like I did for most of last year. But I’m sick. Always tired, often in pain, with flares of allergic type symptoms. I’ve lost the feeling of being well, I can’t remember how long ago I had that feeling. I’ve lost the confidence of knowing how my body is going to respond to something. The confidence I completely took for granted – that I could put shoes on and go wherever I wanted.

I miss walking. I miss heading out the door with no particular destination in mind. I miss walking and keeping on walking. I miss ending up somewhere a long way away, and the satisfaction of aching feet at the end of it, of having got somewhere under my own steam. I miss the quiet of walking. The way I get lost in my own thoughts. The sky above me and how wide it feels. The thinking I do when I walk. How the steady rhythm of my feet on the ground unravels me.

There are other things I miss too. I miss getting up at dawn. I miss the feeling of being able to get up before anybody else and steal some time in the dark quiet. We watched an old episode of Grey’s Anatomy last week and there was a scene where Meredith arrives to start a shift in the pink-grey dawn and I was suddenly gripped with longing. To be out at the first glimpse of morning. To have the whole day stretch out in front of me, all those minutes and hours to do things and go places. I can’t remember how that feels. Did I think that time was mine to eek out to the very last second? I did.

Time is different now. Deadlines come and go. I make dates and arrangements and hope I’ll be able to meet them. I’ve stopped making lists. There’s not much point in planning a day. If a migraine comes, there’s nothing to be done. I make an electrolyte drink, maybe eat something, go to bed. And then I lie there waiting. Hours pass. Days pass, sometimes. Doing nothing except lying. Watching the strange scribbles and blurred waterfalls which move down my eyelids. Maybe listening to a podcast on low and letting the words wash over without making sense. At least the time goes more quickly. That is, it inches.

I’ve ditched the diagnosis I was given when I first got sick. It took me a year but I finally stopped treating the rehab psychologist like a god in my head who must be obeyed or else. He spent one session listening to me and then the next three sessions telling me why I was wrong and how I should think in order to be right. He meant well. But for all my efforts to comply with his ideas about how I should be thinking, I didn’t get better. And when I didn’t get better, my first thought was, it’s my fault. The burden of responsibility for being sick was heavy.

I finally found some hope by doing the opposite of what the psychologist told me to do. I researched. Thanks to that and a good GP I have answers now. Instead of a vague neurological diagnosis I have a diagnosis which fits what is actually going in my body. And a treatment plan that has nothing to do with “thinking right.” I do think, of course I do, and I think in the direction of wellness, because I’m not stupid. But it’s a gentle thinking now, kind thoughts towards the particular white blood cells which are set on overreacting. You’re doing ok, I tell them. We are doing ok.

On New Year’s Eve last year, all those strange days and months ago, Ali and I walked up to the Organ Pipes – the basalt rock formation to the side of Mt Cargill. It was early evening and the sun was heading west. It was incredible to be up so high, to look out over green bush and pasture and hills, and the mountain ranges far off – grey and shadowy against the hazy sky. I looked down at the land as it lifted and fell and thought about how much there is to surmount on a journey by foot, as people once did, way back. And it occurred to me that when we travel by car we lose touch of that sense of actual travel, of our feet trekking up hills and down valleys, one foot after the other.

I had no idea then how this year was going to go, in any of the ways it ended up going. None of us did. At that point I thought 2020 had a promising ring to it! I so badly wanted 2020 to be different from 2019. If 2019 was a place I was trying to get away from I was standing in the airport at the airline counter desperately trying to buy a ticket out right now. I wanted to walk out onto the runway and climb up into a plane. I wanted to watch the door close and not open again until I was somewhere else. Somewhere completely different. Somewhere far away from 2019. Well we all know how that went.

We didn’t go anywhere at all. 2019 just reinvented itself into a year worse than nightmares. And now that we are heading into the final stretch towards December, we can’t help hoping – are we are over the worst? We’re abundantly lucky here in New Zealand, and we know it. We voted our thanks and our belief in science at the weekend. But without a vaccine there’s not much to hope for. And there’s work still to be done. The work of staying vigilant, of keeping things going. The work of supporting those who’ve lost jobs, of loving those who are grieving. The work of listening to those who got sick with COVID-19 and are still sick, months later. The work of supporting those for whom, owing to systemic injustice, the COVID fall-out is greatest.

Standing up at the Organ Pipes at the end of 2019, I thought I had a metaphor. I thought travel by foot was my metaphor for 2020, my metaphor for getting through life. I knew I couldn’t fly out of 2019, I knew there was no escaping anything that quickly. I thought what was needed was a simple process of moving slowly and steadily in the direction of somewhere else, one foot after another. But I never imagined I wouldn’t be able to go anywhere. I had no idea I needed a metaphor for staying put. Yet here I am.

the view from where I was sitting

the view from where I was sitting

It’s so long since I last wrote here. So much has changed. Suddenly the things we thought we could depend on and the ways we reassured ourselves have become less sturdy. I went to the doctor on Monday and could see the stress on her face. Tuesday morning at school our pandemic plan was presented. Now we know when a school will close, what will trigger each respective stage. In January we were reading about a virus which was so far away. Now it is very close, and it’s unlikely that anyone will be unaffected, in some way.

I am wrestling with my own anxiety, and feeling a primal urge to self-isolate – a word which has strong-armed its way into common usage in record time. Self-isolation, social distancing – these were new words yesterday, today they are familiar as the hills. I am not in the category of the most vulnerable, but I still have weird things going on with my health. Even ordinary sickness ramps things up for me. I don’t want to get the virus.

I’ve been pretty germ-phobic since I was pregnant with my eldest sixteen years ago. My midwife had a client who ate a pie in the car after going to the supermarket, without washing her hands first. She caught listeria and lost the baby. Being pregnant is obviously intense – physically and psychologically – and that information coalesced with my heightened state and transformed me. I became germ-phobic overnight. Once I went back teaching, spending all day in contact with hundreds of teenagers, my cautious behaviour increased. I pushed open doors with my feet, pulled down my sleeve to turn door handles. It felt like self-care.

At times I’ve been embarrassed by this behaviour. We now understand that unless you have a dysfunctional immune system, living in a perfectly sanitized environment is dangerous. I wondered, for a while, if I had been overreacting all those years. And yet as we head into a period of unparalleled global emergency caused by a single virus originating from a single source, I’m thinking that all these years of “paranoia” have actually been useful training. I have skills. I can turn a tap on and off with my arm. I already avoid touching my face.

But all the hand washing in the world is not going to completely stop the course of this virus. What we are collectively facing is unprecedented. We are going to lose people. People are going to lose jobs and businesses. The arts community is reeling. The hospitality industry is beginning to reel. One of my best friends has had to postpone her wedding. My dad was due to visit next weekend. Normal, whatever normal looked like for each of us, has gone. I can feel it in my gut, it’s a heavy wariness. The world is going to look very different when we come out the other side of this.

I’m not religious like I used to be, and that’s a good thing. But I still pray. And somehow it’s one of the few things that make sense for me right now. It’s not that I think my sitting quietly is going to change anything external to me (although I hold space for the possibility), it’s just that I have to do something. I can’t think of the families who have lost or will lose loved ones and do nothing. I can’t think about those facing the loss of their income or their life’s work and do nothing. So I pray. I pray a simple version of the lovingkindness prayer, thinking of a person, or a group of people.

May you be happy. May you be safe. May you be healthy. May you live a life of ease.

It seems impossible to think about a life of ease right now. But perhaps it’s the right thing to ask for, even if it’s only relative ease, or ease in a small detail, or ease in spite of what’s going on, or ease on the inside of us, when the outside is so unpredictable.

The Friday morning before the mosque shooting I walked with Abigail to school, along North Road and all the way up Blacks Road. I was completely out of breath, but so alive and mobile after months of sickness it was incredible. From the top I could see across the valley to the hills on the western side of town, repeating slopes of white squares and green, and just visible the grey blur of the hospital building of the rehab ward I stayed in.

I put Jean-Michel Jarre on to walk back down the hill, and as I was walking I realised it was the kind of music I would have listened to on my walkman bussing home from school in 1992, my final year of high school. The year which could have meant so many different things, could have given birth to so many different parts of me, could have opened up the wildness I hid inside. But it didn’t.

The music was trippy in my ears as I walked steady down the road, and I kept thinking about that time, when I loved The Pet Shop Boys and wrote strange little stories, and constantly talked to myself in my head. That was the year I could have known I was attracted to women. The year I could have had some sort of plan about what I wanted to do with my life. But there was so much I was avoiding about myself, so much I didn’t understand.

That Friday afternoon news about the shooting started filtering through. Our first reaction was puzzled disbelief, and then as the number of victims continued to rise, total shock and dismay. We shouldn’t watch too much of the news, we said, as our fingers kept hitting refresh on our phones. We should try to distract ourselves, we said. But the number kept growing.

The weekend went by in a daze, and on Sunday morning we went to church. We needed peace, and space to process. We wanted to share our grief, not wrestle with it alone. The choir sang Pleni sunt coeli – Heaven and earth are full of your glory – Dona nobis pacem – give us peace, and I cried. After church we bought three bunches of what was left of the flowers in the New World Supermarket on St Andrew’s Street and took them to the Al-Huda Mosque only a few blocks away. What else was there to do?

The focus of the morning’s service had been the image of God as mother hen, wings stretched over her chicks. The text was taken from the book of Mathew, where Christ is recorded saying “Jerusalem, Jerusalem… how often have I longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wing.” The text was poignant for two reasons, one being that the city of Jerusalem is sacred to all three Abrahamic faiths, the other being that the image of God as mother hen is one of the most tender of the feminine images of God in the bible. And oh how we wished she could have gathered her children away from that Friday afternoon.

The service kept referring back to the tragedy, and to the Islamic communities in Christchurch and Dunedin. It was a human response to the horror more than a Christian one, and that felt right. The verb the minister returned to as he expanded on the text was gathering. He asked a question: how can we be a people who gather under the wings of God? What a question it was. I picked up my phone and typed it into a note, and as I typed it I thought of how the question would read if we replaced “God” with “Love.” How can we be a people who gather under the wings of Love? What would that look like?

Around that time I’d been thinking about the parable of the lost coin, the story the book of Mathew recounts Christ teaching. In it a peasant woman has lost a valuable coin, and sweeps every inch of her house to find it. An engraving by the English painter Millais has her with a broom, bent over a candle. The room is dark, and through the window above are stormy clouds. A traditional reading of the story would have God as the woman searching, us frail humans the lost coin.

It occurred to me as I was walking that Friday morning, while I was thinking about 1992 and everything I was avoiding in myself back then, that if God is in me, as I believe God is in all, then I am both the woman sweeping and the lost coin. And I have been looking for myself all along. Searching diligently. Sweeping and turning and looking. I’ve had the broom. I’ve had the candle. The sky was wild and dark, but I found myself. Or should I say, I keep finding myself.

I’ve said this kind of thing so many times here it feels like a truism. But I got sick in October and didn’t really start recovering until April, so I’m in the mood for telling the truth. The six months between October and April disappeared in a blur of fatigue and vertigo and trouble walking. Most of these symptoms were functional, which is another way of saying we don’t really understand why. But the symptoms were as real as the hard ridge that formed underneath my right little toe from limping for so long.

So I’ll tell you what I think. I think the gathering of the mother hen is a similar action to the searching of the woman looking for her lost coin. The mother hen is bent on drawing in, collecting, gathering all of her chicks, and the woman searching for the lost coin is gathering too – collecting, searching and sweeping. If we can see ourselves in both the woman and the coin, then we can see ourselves in both the hen and the chicks. It’s not an either/or. We are not bound to the passive, dependent role, our rescue always from outside of ourselves. No, we get to do the gathering too. We can, if we choose to, search out and gather together all the parts of ourselves. Collecting and drawing in what we’ve avoided and repressed and misunderstood.

The white gunman who planned and carried out the mosque shooting in Christchurch had been a resident of Dunedin. His car was registered to an address in Sommerville Street. That’s not my street. I don’t live there. But if he had been my neighbor, I have this heavy feeling I would have avoided him. I don’t know what to do about that. I’m sorry. And I’m wording this carefully, so as not to be insensitive to the trauma and grief of others, but I want you to know I’ve begun to gather myself together. I’ve stopped avoiding myself. I’m carefully drawing in the disparate parts of me, even the ones I avoided for so long. And maybe that helps? It might help.

Warrington, Monday 16th July

Warrington, Monday 16th July

I’ve taken a while to find myself. I was looking for so long. I caught snatches every so often, glimpses of my reflection in the still water of calm, when the calm found me. There were moments when my reflection was so vivid, so arresting in it’s me-ness that I thought I’d actually found myself, but then the image would inevitably fade, and things would grow murky again.

It was like searching for something through silty water. Every time I took a step forward my movement stirred the mud again, and there I was, seemingly no wiser than before I took the step. And yet perhaps it wasn’t so futile. Perhaps it was more like the kind of methodical turning over that happens in an archaeological dig. Laboriously scraping back layer after layer, not with the infinite care of a professional about to uncover some world treasure, but with the desperation of someone who knows they have yet to live. Each layer compelled me downwards. My nails were caked.

I saw The Return of the Jedi at the Civic Theatre with my dad when I was eight. I remember it was eight because it was the first movie I ever saw in a theatre and the event played a starring role in my childhood folklore. I didn’t go to the movies until I was eight. My mum didn’t let me because she said going to the movies was evil. What a movie to see on my first trip to the cinema. And what a theatre! I could take you to our seats today. Upstairs just left of the middle, about three rows below the aisle. Peering down at the golden lions either side of the stage, eyes glowing, and back up to the midnight sky above, those tiny blinking stars calling me into my imagination.

What an invitation! And I heard it loud and clear! My saving grace through those early years was my imagination. Through it I rescued myself, as often as I could. I was like the dancing princesses, in the collection of Grimm’s Fairly Tales gifted to me on my eighth birthday, who escaped from their beds every night and danced until dawn. I was like them because I could escape. I could take myself away, up into the wide open spaces of my mind. And reading was the best way of doing that. Dear Moonface. Dear Uncle Bilbo. Dear Muffie Mouse. Dear Wombles, all of you.

There were so many things that happened the year I turned eight. As I sit here writing it down I find myself wondering if it really all happened in one year. But this is my story, not a historical account, so here’s a list. I had a sleep over at my friend Celina’s who lived around the corner. We slept in a tent in her garden and were awake until after 11pm. I know because I saw it on the digital clock on the dresser in her parents’ bedroom which we kept getting up to visit, even after they’d gone to sleep. One weekend my mum made homemade ice-cream, chocolate chip mint, icy and sweet and we shared it with the kids from next door.

Other things happened. I watched the old woman next door water the garden with an empty kettle. My dad came back to New Zealand and my mother wouldn’t let me see him. He turned up at our flat one day with a present for my birthday and I sat on the lounge floor frozen, while he and my mother talked in low tones at the back door. Go and see your father, said the friend of my mother’s who was visiting. Go and see your father. But I couldn’t move a muscle. How could I? That was the year I lay awake for hours most nights, sleep as far away as the moon. When the heavy weight of sadness descended in the evenings as the sun went down, the same weight I recognised as depression much later.

I have often wondered why my fairly ordinary childhood gave me so much to work through. Everyone else around me seemed to be getting on with things pretty easily. Other people with more tragedy in their lives than I’d experienced, or perhaps more obvious tragedy, seemed more resilient. I grew up timid, anxious, shy, and more than all of those things; acutely sensitive. I managed to build a kind of armour around myself as a teenager, but it was mostly bravado, and a thin bravado at that. Underneath I was all open and aching heart.

I’m reading The Choice, by Edith Eger, a survivor of the Holocaust. It’s an incredible book, not just because of the power of her story, but because she narrates it as a psychologist, from the perspective of someone who has worked through her own story and also walked alongside others as they do the same. Something early on in the book moved me to tears. “There is no hierarchy of suffering,” she writes. “There’s nothing that makes my pain worse or better than yours, no graph on which we can plot the relative importance of one sorrow versus another…I don’t want you to hear my story and say, ‘My own suffering is less significant.’ I want you to hear my story and say, ‘If she can do it, then so can I!’” Her words gave me permission to tell my story as it is, without shame or excuses. And with that permission came a rush of self-compassion.

There was an evening earlier this year when I’d been hurt by something. Something ordinary became a trigger of enormous proportions and I was completely adrift in a sea of grief. The pain was extreme. I tried to make sense of my hurt, tried to rationalise it. Tried to figure out why it felt so bad. I’ve been aware of the little girl inside me for a while now, and as I slowed my thinking down I realised how terrified she was right in that moment. Terrified that she was all alone, terrified that there was nobody who could help her. A memory came flooding back. The scariest scene in The Last Jedi. Jabba the Hut’s pit, and that awful monster with the sucking tendrils at the bottom. And there I saw myself; a little girl holding on to the side of that pit for dear life, about to fall in.

There’s fear and then there’s terror. This was terror. It was completely overwhelming. It wanted to swallow me up. It wanted me to fall into it and never get out again. It was the fear beneath the fears. The terror that had lurked behind every loss and hurt that followed. And I was finally feeling it. Finally, I could witness that terrified little girl.

What happened after I saw myself on that edge is the kind of thing that can happen to any of us, when the circumstances are right. I was with my partner, and she was holding me. It wasn’t so much the words she said as the fact that I knew I was with a wise witness. Somehow her presence helped me to see that the moment I was in was sacred. That it wasn’t to be avoided or run away from. Suddenly I could see that I’d been waiting to get to this place all my life, and that now I was here, there was work to be done. Holy, magic, soulful work. The work that can change the course of a life.

So I focused on that girl, that dear, terrified girl. Holding on so tightly because if she didn’t hold on tight she would fall in and never get out again. And as I watched her, I saw angels. Angels. They weren’t doing anything. They weren’t trying to rescue her or even stop her falling, they were just being with her. Being with me. Because being there, witnessing her, and letting myself feel that terror was one of the bravest things I’d ever done. The angels confirmed that. They were there because what I was doing was important.

Then I looked up and saw I wasn’t alone. There were people just above me at the top of the pit. They were the people who I knew loved me and would help me if I asked. There weren’t many of them, but I didn’t need many. I just needed to know I wasn’t alone. And then one of them stepped forward. The most important one of them all. Me. Forty-four year old me to be exact. With the most exquisite look of calm determination on her face as she walked towards the edge. She climbed over and let herself down to where I was holding on, picked me up, and wrapped me in her arms. I was found.

I’ve taken a while to find myself. I’ve been looking for so long. It’s a life’s work. One I won’t ever completely finish. And yet there are moments along the way, like this one right now, when I know I’ve got somewhere significant. When I know I’ve seen something important, and rather than ignore or hide I’ve faced it, head on. And in the facing of it I find myself, right there at the centre of the pain. Each time is incredible. Like a homecoming and a reunion and an unveiling, all at once. I am witness and rescuer. Every time.

I’m sitting up in bed watching the light. The early morning light, the light through the tall windows of this villa front bedroom, through the gauze of the net curtains; dappled where it travelled the branches of the sour cherry outside the window, making an obtuse triangle on the wall opposite, the shadow of branches playing lightly across.

There is washing on, more washing. Washing folded and put away earlier while I waited for the kettle to boil. New sheets out ready to replace the ones I am sitting on here, and a full load of washing nearly dry on the line that I put out last night. The dregs of the dishes the girls washed the night before last sit dry as a bone in the dishrack, waiting to be put away. The vacuum cleaner sits patiently in a corner of the dining room, soon to be used. These are the ways I love my house.

There are no children to be fed today, none standing at the bench right now helping themselves to too much yoghurt, a third of a block of cheese, almost an entire cucumber. Their loud music is not on in the kitchen, they are not lying about in the lounge in their pyjamas watching youtube. Their bedroom floors are not strewn with yesterday’s clothes and last night’s books. They are simply not here. The only noise, save these fingers typing, is outside. Birds in the garden, every now and then a car down on the main road.

A bowl of fruit salad waits for me in the fridge, a breakfast gift. Made by the girls last night at Pat’s place. I might see them today. They still have only one of most things. Togs, sun hats, most-loved soft toys, currently-read books, favourite clothes. These things they drag with them from his place to mine, or mine to his, at the beginning of every week. Or go back for if something’s been forgotten. Oh how modern it is, how twenty-first century, to grow up living in two houses.

What have I done? I have irrevocably altered the fabric of their lives. I did this not by coming out, not by moving into my own bedroom and then dragging us over town to a bigger house with a bedroom for all of us. They hardly blinked at that. No, it was moving out that changed things the most. And it was the conversations that happened leading up to the move which caused the most consternation. That was when this shit got real.

You talk to a woman who’s been the key player in the break-up of her family and ask her about the reaction she received. You can be sure she will have stories of sideways glances at the school playground, a dwindling number of friends who call, and from those who do, a steady barrage of unsolicited advice. She will tell you how it feels to be the recipient of someone else’s anxiety, about loaded questions which say more about the questioner than her own actual situation. We might be in the twenty-first century but we still have an unwritten rule that mothers don’t rock the boat, that mothers suck it up. And above all, that a mother can be true to herself only as much as her truth doesn’t “damage” her children.

There was no room for me in that big house with a bedroom for everyone, as big as it was. Physical space does not automatically create psychological space. And the unfolding of something new cannot always happen in the midst of the familiar. That house was a Noah’s ark for us as the family-that-was, it held us together as we rocked back and forth through an entire year post my coming out. A year in separate bedrooms, a year to reel and fight and grieve, a year to give the girls the time to accept this unwanted change. A year for me to clear my head, to figure out exactly what everything meant.

That we stayed together for so long, in some semblance of what we were, is a credit to Pat. Bit by bit he found a way to get his head around the enormous disruption my coming out had caused. But I engineered that year together, I found the house and made it happen. And I did it partly for me, to give me time to listen to myself and to re-group. But really I did it because I wasn’t ready to break us. I wasn’t ready to break anything. I was trying to hold us all together. I had caused the fall, and I thought I could somehow run around and catch us too.

I moved out in November – on the anniversary of my coming out to Pat. I packed up my things, my books and bookcases, my journals and photo albums and boxes of ferreted-away mementos. I took what was needed to function as a household, to be a subset of what was. I had to buy a fridge and a bit more furniture, but not much. And the first weekend I moved into the new house – the villa next door – the girls came too. That was the start of their first week with me, and along with the dog they’ve done 50/50 between houses since then.

Are they ok? That’s a good question. But it’s a question to ask them, and not for a few years yet. My coming out and subsequent breaking of the family will leave an indelible mark. It will be a big chapter in the story of their lives. A chapter marked with bold caps and expletive emojis. A chapter peopled with anxiety and grief. I’m so sorry about that chapter. I’m so sorry it will be there because of me. And yet I’m most interested in the chapter that will come afterwards. I wait and watch with anticipation and pride as they write it every day. They are brave and they are bold and they are becoming themselves.

Meanwhile, I get to start again. How do I want to live? Who do I want to love? What is most important to me and how will I make that happen? These are the decisions I get to make here in my own house, in my own space, in my own new beginning. These are the decisions I make now as I write these words sitting on this bed, the light pouring in. I make them for myself and I make them for my girls. I show them how to live.

Corsair Bay, January 2017

Let me tell you about coming out. About waking up in the middle of the night in the second week of that brave new world, and sitting up suddenly in bed, eyes wide. I’m gay, I whispered into the darkness. I’m actually gay. And suddenly I found myself on my knees beside the bed, hands clasped. I want to live my best life. I want to live my actual life. It was a prayer. A promise. My vow to me.

How did I do it? How did I do those first days of knowing, sludging through grief and shock, not breathing a word out loud. Panicked and stricken with every thought of the future, every thing that would not be. All the plans so tenderly hoped for. Every goal we’d worked so hard for. And the girls. The girls. I told Pat late on a Saturday evening in November, over a year ago now. After a long day of waiting, knowing it was time to tell him the truth. After writing it in my journal for the first time that morning; I’m gay. And then saying those brand new words out loud to a friend that afternoon. I couldn’t go a moment longer without telling him.

It was like there had been a death in the family, we both felt it. The words had come out quickly, tumbled out clumsily, because there was no point in prolonging anything. I’ve realised I’m gay, I said. You know the thing I was upset about last weekend, I’ve realised why I was so upset about it. It’s because there’s something I’m wanting that’s more than what I have in my life right now. I want to be in a relationship with a woman. I’m gay. And we both sat there stunned.

We went on our own journeys of mourning. It was the hardest thing to see him hurting because of what I’d done, and not be able to do anything about it. I moved out of our bedroom. First to the couch in the lounge, with my pile of books and hairbrush and things perched on the edge of the bookcase. Then into what had been his office. First on a mattress on the floor, then on a bed of my own, single, for the first time in 17 years. One day I went back into what had been our bedroom to get some clothes and I stood at the dresser and looked over at the space where my bedside table used to be, where I had sat up in bed all those hours writing, working on my thesis. That space which had been so nurturing, so wholly mine. And I fell on my knees at the end of the bed and wept.

There was never enough crying. I never got to the end of it. Not the first week before I told a soul, when I cried whenever I was somewhere no one could see me, nor the weeks after as I settled into my new room. There were always more tears. It was a private grief, hidden from the world. Isolated and utterly lonely. It was the only way I knew. I had to do the work on my own.

And I did it thoroughly. Writing screeds in my journal. Re-reading back over years of old journals, remembering the marriage that was. How hard we worked. How much it cost. There were therapist sessions by skype, and long conversations with a few close friends. Nobody questioned what I was doing. Everyone who knew me could see it was the truth. Everyone who knew me could see I was doing exactly the thing I needed to do to stay alive. I was rescuing myself. I was giving myself a life.

I took the girls to Christchurch for a few days that January. It’s our big smoke now that we live in the South and we love it. We are regulars at the Christchurch Art Gallery and the Margaret Mahy Park, and at my sister’s place over by the beach, where weather-beaten houses perch beside wild sand dunes. It was my first trip away with the girls since coming out, and I knew somewhere deep down that it was a taste of a new way of being family, of the new shape that would eventually form out of the ashes of what was. And I’m always up for an adventure. The road was what I needed.

For a dark moment somewhere between the December after I came out and the January of a new year, I faltered. The thought of everything I was breaking was almost paralysing. I was taking what I had worked so hard to build and ripping it apart with my very own hands. I couldn’t fathom it. It was excruciating. And yet as I wondered if I could just take the words back, pretend I’d never said them, pretend I could carry on as I was, I felt the shadow of depression cloud over me somewhere. I realised that to go back was to go down. I knew that if I didn’t keep moving forwards something dark and empty would suck me under.

I drove away from my sister’s place one evening and instead of carrying on to where we were staying I took the tunnel road through the Port Hills to Lyttleton. I had the sudden urge to explore, to go somewhere I’d never been before. What a surprise it was to see the tunnel open up to the harbour and the port below, the broad mass of ordered logs waiting on the way to somewhere else. The hills on the other side were warm in the setting light, beckoning, hinting at hidden bays behind soft curves. I kept driving until we got to Corsair Bay. The carpark was staggered in layers, and the slope of the land led our eyes down to a thick band of trees which I knew must hide the beach below. I wanted to see it.

We walked a worn path down through the trees, passing families making their way back up, arms filled with the paraphernalia needed for a day at the beach. Below the trees was an old concrete sea wall, tracing the shape of the small bay, the water and harbour reaching out beyond it. I sat on the edge and watched the girls paddle in the dark and silky water. There was a fixed raft out where the bay opened to the harbour, and people were still swimming out there in the fading light. I saw a couple of swimmers even further than the raft. Swimming in a straight line towards the moored boats. This was their regular exercise, I imagined. These swimmers were owning the wild space that was the broad expanse of harbour. They were not content with the shallows.

I could have stayed in that old, familiar life. But what kind of life would it have been? What stories would I have written? Not the ones I’m writing now. Not the ones that wait, just below the surface of things. The ones I will write now that finally I know who I am. Would you have wished a half-life for me? Would anyone who really knew me be happy for me to live any less than the wild and broad life that waits for me? But I didn’t do it for you.

All those years led me. The marriage, the family, the building and the stretching and the growing up. I gave my best. I was faithful. And look what came out of it; three incredible women. Three women who are growing up too, who will take a path towards themselves and, I can only hope, not waver.

From the 16th to the 18th of November I cried. In the car, walking the dog, in the toilets at work. In the shower, cooking dinner, hanging out the washing. Wherever I was where no one could see me.

On the 19th of November I got up in the morning and vacuumed the lounge. I hung out a small load of washing on the drying rack in front of the window. I drove into town for Greer’s end of year dance show. At the library afterwards a blue spine caught my eye out of a pile of withdrawn books. The subtitle; Coming out in the Anglican Church. For a moment, my whole body came alive. I bought the book.

At about two o’clock I drove across town and up the hill to my friend’s house. Together we went to the gardens, where tall trees lean over the edge and green shrubs produce bold flowers beside curves of grass. We sat on a bench in the sun looking out. I opened my mouth. I said something I’d never said out loud before. I’ve realised I’m gay, I said. Deep down I know I’m longing to be with a woman. We cried.

Dinner was chicken and vegetables, roasted by Pat back at our little bungalow on the other side of the hills. We ate it together, all five of us around the small borrowed table in the corner of the lounge. It was a normal Saturday night, except that we both knew we needed to talk. We waited, me skulking, obsessively tidying, waiting for the girls to sleep. It was a long evening.

There wasn’t much to say. I just had to get it out. I have a deep desire to be with a woman. I’m not bi, I’m gay, I said. The words were clipped, serious. His face fell. He stood up. He paced the room. What is that supposed to mean? He said. What does that even mean? He sat back down on the couch. I told him everything I knew. He listened.

It was like taking our future into my bare arms and throwing it off the edge of a precipice. We both watched as it fell, broken faces. But neither of us reached up to grab it. Once I had let it go, we could not pick it up.

We cried. We kept crying. I sat there watching him, knowing exactly what I had done. Wishing like anything I could do something to take it back. But there was nothing I could do. Once the words were out, they were out.

Let’s take communion, I said. I went to the kitchen and came back with a plate. Two squares of bread on it, two glasses of juice. It was a meal of desperation. I think I said God help us. After that we played a round of scrabble, my idea. I wanted us to stay on the couch. I felt like once we got up off the couch it would be the end.

But it wasn’t the end.

* * *

I wonder now how the stories will go. All the half-written essays. The one about flying and telling the truth. The one that whispered to me every time I tried to finish it; really? Are you really telling the truth? How will the stories go now that I know who I am? Now that I’m here.

Let me tell you about beautiful women. Soft faces, whole worlds behind clear eyes. That little bit of smooth skin at the waist. I got to see my friend. She was going but I saw her before she left. She was on her way but she was so present sitting next to me. Ella took a photo of us: smiling wide and beautiful. My friend had no idea what I’d realised about myself. I sat next to her smiling and knew without saying a thing. She was beautiful to me. She is beautiful to me.

To be unable to speak those words: she is beautiful. This was my life. From the age of ten, when I saw a woman’s naked breast for the first time. I can still remember the line of it as she turned towards me. Beautiful, I thought, but couldn’t say. Then later, a friend, I loved to watch her mouth when she read her poetry. Beautiful, everything in me knew it. But did I let myself know it?

And in between, all the girlfriends I loved dearly and wondered why the friendship never came back to me in quite the way I gave it. What was missing? Why did I love them so much? I never knew. They were beautiful to me. But I couldn’t say it.

I went on a Sunday school camp with a friend. We were ten or eleven. We talked late one night in two top bunks, head to head. Her voice was soft and her face was kind. I asked her if she wanted to hold my hand and she did. We fell asleep, hands clasped. It was heaven. There was nothing in it. Oh but there was everything in it. The kindness of a friend. A picture of intimacy. A clue like a magic stone I wouldn’t pick up until more than thirty years later.

What is it like to live for so many years without putting voice to a longing? What is it like to feel something but have no words for it? What is it like to feel something and simultaneously reject it? To nullify it instantly? To feel it and unfeel it at exactly the same time?

It is like wrapping yourself up in bandages. Winding the pressing grey weave tight. Winding it tight, layer over layer. This is wrong, this is a feeling I am not feeling. I am not feeling this feeling. Over and over. Tight and covered.

Give me a roomful of women. Give me a world of women. Give me one soft hand; my own. Let me clasp it, soft on soft, all my own. This is how I learn to love a woman, by learning to love myself.

* * *

On the 18th of November I started listening to Sinead O’Connor on IV through my headphones while I sat working in the staffroom. Working face down so that no one could see my dark eyes. Take me to church. The ones that don’t hurt. I don’t want to love the way I’ve loved before. Hitting refresh over and over. Dragging myself to classes and then hiding away as soon as they were over.

On the 21st of November I changed the song. There’s no safety to be acquired. Riding streetcars of desire. I have chosen, I have chosen, to become the one I’m longing. And in the moment I first heard it, I knew. What did I know?

I knew that I had chosen to become what I was longing for. To become her. To become the one who takes my hand, the one who loves me back the way I love her. The one who watches me, the one who knows how beautiful I am.

Tell me, how does that go? How do I do that? Who will teach me?

* * *

I looked for a picture to go with this essay. I wanted to be in the picture. The picture needed to be of me. And it needed to be close to the time I am describing here, a picture from before I said the words out loud to all of you, I am lesbian. I scrolled through image after image on my phone. Searching for myself. Where was I?

All I could find was a picture of my feet. It was my birthday, a whole year ago, and we were at the beach. A wild day, windy and grey. We were right out on the edge of everything, facing the arctic. I was happy to be there, happy to be with my family. But I spent most of that day with an ache I couldn’t name. Something was missing.

You might think my story is commonplace. Plenty of people come out later in life. Coming out, in our moderate nation anyway, is now a familiar cultural event. It’s not so unusual. Or perhaps you’re on the other side of things and think my story is broken. That I’ve broken my family. Perhaps you think I could have asked for help. Perhaps you think I could have changed.

But none of you have any idea how much I want to live.

I’ve been writing about giving birth to myself for a while now. Every year for the last five years I’ve dragged myself out of whatever muck I was wading through at the time and come out the other side feeling like an arrival. Grimy with vermix and sucking in air like my life depended on it.

And then I actually came out. I said the most astonishing words. Astonishing to me, anyway. I’m gay, I said out loud for the first time on Saturday the 19th of November 2016. 100% lesbian, I wrote in emails to friends in June 2017. The arrival of arrivals.

I’ve spent every year since 2012 playing detective on the case of me. It’s a blink of time, in many ways, but a long hard slog all the way. There were some foul truths about my childhood I had to name. To carry on without naming them was to be complicit in my own injury. To leave them unspoken was to leave the blame on the child I was – who believed it her fault.

So something had to change. If I was going to actually live. I had to give up playing stop-gap for my broken past and let it stand on its own. It was a brutal thing to do. Nobody who featured there was going to thank for me for it. Every family feeds off its own fantasy, to some extent, because memory is always part fiction. The bank of shared memories a family raises like a banner to the world; this is us, is curated by the subconscious. What the mind can’t cope with, the mind forgets.

But I never really forgot. I left myself clues at various layers of consciousness and each layer uncovered propelled me down to the next. It was surreal. Scores of memories along the way that had sat patiently waiting to be apprehended. Seemingly without purpose or meaning until I was ready to understand.

Like the memory of seeing a woman naked for the first time, apart from my mother or step-mother, and how beautiful she was. Like the time I played families with my friend at primary school – she dad, I mum – and the feeling was electric. Like the time I was twenty-one or twenty-two and joked with a girlfriend recently married, oh I’ve always wanted a wife, and she looked at me strangely. As soon as I uncovered the truth; I am lesbian, the memories bubbled up. And they added to that truth; I always have been.

What an awkward and lonely journey. Some days I feel like the only person in the world who has her head in the past like it’s one of those airport thrillers, reading with a fine tooth comb. But of course I’m not. There are plenty of us, and perhaps you are one of them. We scour the pages of the past because something somewhere doesn’t add up. Or because something somewhere has to change.

The journey backwards has nothing to do with blame, and everything to do with owning or refusing to own. I own my sensitivities, for example, but I refuse to own the lack of understanding on the part of those who were charged with my care. I own my compliant personality, but I will not own the way my compliance was taken advantage of. I own my impetuousness and my dreamy other-worldliness, but not the criticism and punishment that was laid down heavily for it. To do so would be to join those voices in my own judgement. I already did that, for too long.

So when I say, here I am, it’s my birthday tomorrow and I’m born again, the words are not light-hearted. I might have said it in a similar way before here on this page, but that’s because it’s a process, the journey of a life. I’ve felt out of synch with most of the people around me for a long time. This journey is not one that makes easy dinner-table conversation, it’s not the kind of talk that goes with a coffee on a Sunday morning. But I’m not ashamed of it any more.

In re-naming my birthday my “giving birth-to-myself” day I’m not displacing my mother. A mother is a mother, is always a mother. She had the sex that conceived me, chose to keep me, carried me and pushed me out in a foreign country. She brought me halfway round the world to home, found rock-bottom and then to her great relief, found the rescue she’d been longing for all her life. And as she forged forwards without looking back, running on limited resources and support, something important inside of me was broken. This is my story.

I was her partner in all of it. I have memories: vivid memories, sense memories, strange surreal knowings that go right back to the beginning. My world was her world, we were twins in the same sac. Her sadness was my sadness, her happiness my joy, her anger my pain. Until I realised it wasn’t. Until I realised her world wasn’t my world. Until I realised in shock and awe that my world was waiting for me. That my life was yet to be lived. And so I bust myself out.

We can live, without really living. We can speak, without really saying anything. We can spend our lives smiling and nodding and keeping ourselves busy. Babies, houses, renovating, de-cluttering. We can pour enormous amounts of energy into things that seem so productive; relationships, projects, addictions, other people, other people’s projects, and never pour an ounce of energy into our own actual lives. The ones that only we can live. The ones that wait empty and static until we bear down and push ourselves out.

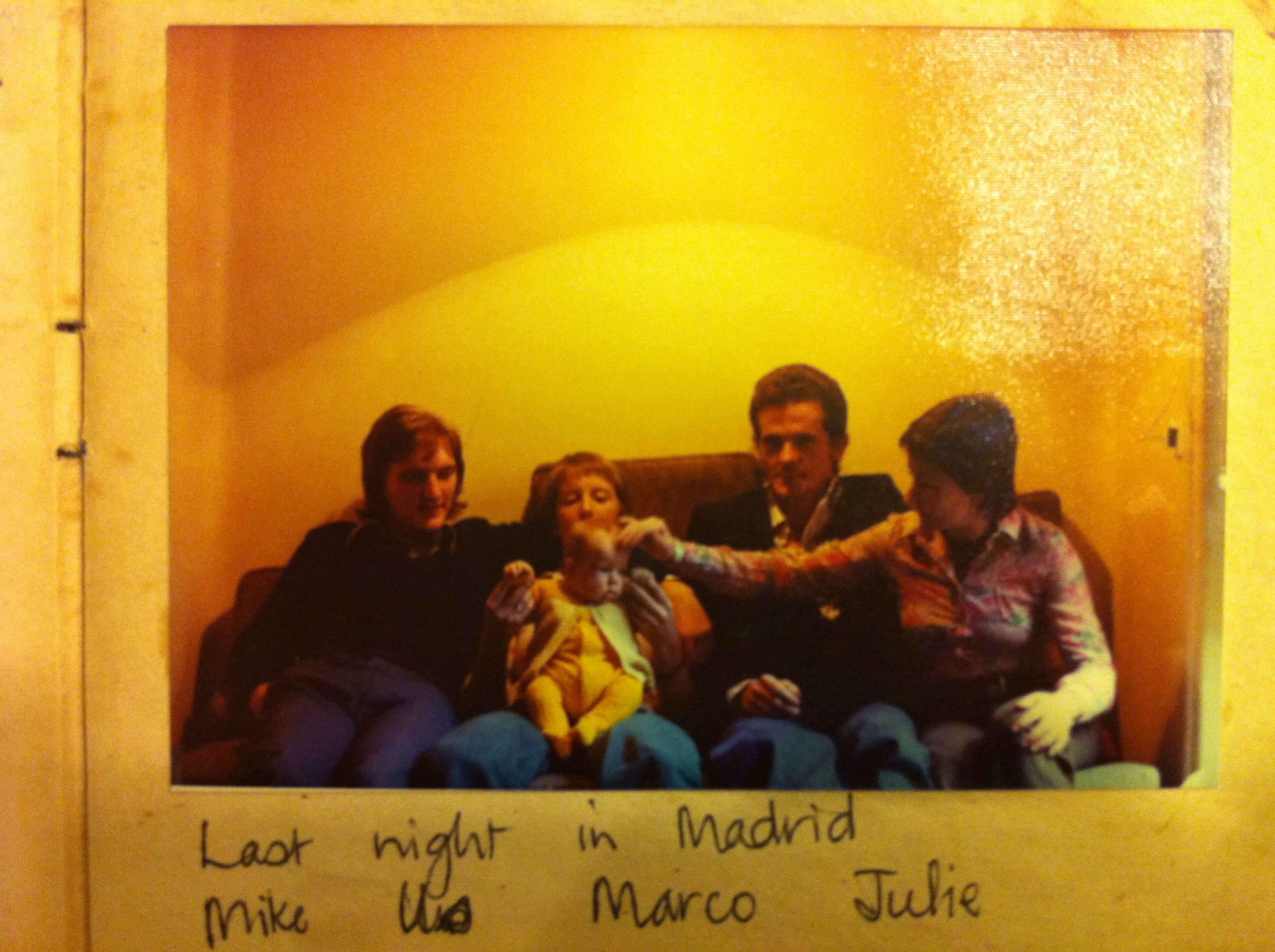

When I look at that photo above, Last night in Madrid, a funny kind of knowing comes over me. There’s something I remember about that night. The muted light, the energy, the momentary connection between people in time and space like a spiral at its tight core about to be thrust outwards. My father behind the camera, my step-mother reaching out to stroke my forehead. My mother holding me tight. You can see I was loved. You can see how important I was, how much I had to teach this bunch of wild kids. My mother chose me, and so I came. The prophet-storyteller had arrived.

I tell them they can love whoever they want. I tell them they don’t have to love, that their lives can be rich and full as they are to themselves, without needing to be attached or partnered or taken. I tell them they are beautiful, just the way they are. And they dance up the hallway singing last Friday night, we were kissing in the bar and they stop at the mirror and they preen.

The eldest asked when she could buy her first lipstick. But you’re beautiful without it, I protested. My lips are pale, she said. I didn’t ask who she wanted them to look bright for. The middle one asked me if I wear lipstick to work and I said yes, sometimes. I put it on when I get there, I said. I can’t be bothered stopping before that. Mostly I just can’t be bothered.

The mirror tells me what I am. A woman who has passed the forty mark, who has little time for appearances, who pays attention to the bare essentials: clean hair, wide smile, clothes assembled with a nod to form and interest. I can see the evidence of the years, the line between my eyebrows, the mole on my chin. Underneath the clothes there is more evidence. The silver lines at the top of my thighs. The soft round of crumpled belly, a gift from my daughters.

I wouldn’t trade these markers for anything, not for all the youth in the world. I think back to the days when I stood in front of the mirror and doubted, and I feel tired. You couldn’t take me back there, I would never go. The mirror is now nothing more than a tool, no longer the reflection of my worst critic, no longer fodder for all those taunting voices; not good enough, not pretty enough, not tall enough, not skinny enough.

He is the morning parent. He slices the cheese for her lunch. He wraps it in tin foil so that it doesn’t make the crackers go soft. He cuts the apple into wedges and then puts the whole fruit back together with a rubber band because she won’t eat it brown. Then he masterminds the logistics; music practice, lunchboxes, raincoats, getting out the door. He is also the nurse of the family. The one most deft at cutting medical tape. He is more inclined to take a sick child to the doctor. He worries.

I realised, not so long ago, that if I didn’t show my daughters how to live, what good was I? That if I didn’t live, my whole actual real life, that I was failing them. And so I get up first in the morning and head down the path to the car in the murky grey light of not-quite-morning. I often work in the weekend as well. Some times in a quiet corner of the library, and other times at home in my study with the door ajar, and then they know the music has to be quiet and there’s no yelling in the hallway.

They brush their teeth when I’m in the shower and I do not hide. They like to touch my belly and they know it’s soft because I held each of them inside me for weeks and weeks, long enough for them to grow entire. They hardly notice the scar that runs down my spine, or the messy one above my hip, faded purple. I’ve told them they’re from an operation, but they don’t care. They haven’t noticed how crooked I am, how one shoulder always droops slightly. They think I’m beautiful.

My daughters know that if I hadn’t married their dad I’d have eventually fallen in love with a woman. Sexuality is something we’ve talked about with them since they were old enough to understand. They knew when I thought of myself as bisexual, and I told them the truth when I realised I was lesbian. We’ve always explained that most people grow up to love someone of the opposite sex but that some find they love someone of the same sex and that’s no big deal. We’ve made sure they know they are free to make up their own minds about who they love and they like this knowledge. I can see it on their faces, that it’s one more thing that makes them strong.

My daughters like to stand in front of the mirror, especially the eldest one. Sometimes I have to bite my tongue and hold back words about wasting time. But then I see how her eyes light up as she meets her own gaze, how her face softens and her chin lifts as she appraises herself from all angles. I think I understand now – I hope I understand – how important this is. That this is something she needs to figure out. That the voice she needs to hear in her head is her own. She wants to answer the nagging question am I beautiful? with a resounding yes.